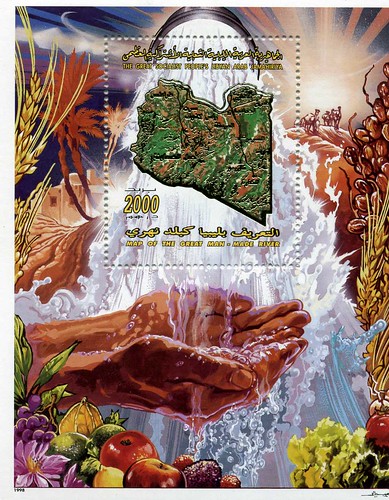

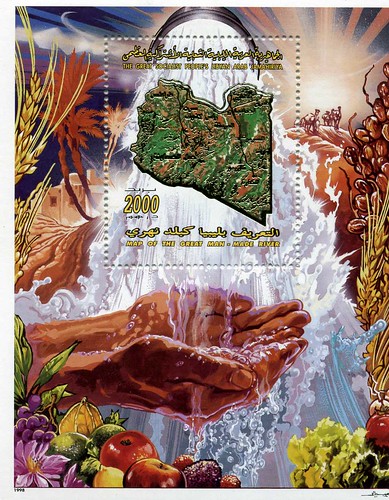

the GREAT MADMAN’S RIVER PROJECT

Few in the West may know that Libya – along with Egypt – sits over the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer; that is, an ocean of extremely valuable fresh water. Control of the aquifer is priceless. This Water Pipelineistan – buried underground deep in the desert along 4,000 km – is the Great Man-Made River Project (GMMRP), which Gaddafi built for $25 billion without borrowing a single cent from the IMF or the World Bank (what a bad example for the developing world). The GMMRP supplies Tripoli, Benghazi and the whole Libyan coastline. The amount of water is estimated by scientists to be the equivalent to 200 years of water flowing down the Nile. Compare this to the so-called three sisters – Veolia (formerly Vivendi), Suez Ondeo (formerly Generale des Eaux) and Saur – the French companies that control over 40% of the global water market. All eyes must imperatively focus on whether these pipelines are bombed. An extremely possible scenario is that if they are, juicy “reconstruction” contracts will benefit France. That will be the final step to privatize all this – for the moment free – water.

In the middle of the Libyan Desert’s scorched yellow sands, rows of green grapes dangle off vines; almond trees blossom in neat lines, and pear tree orchards stretch into the distance. Libya is one of the driest countries on Earth, bereft of rivers, lakes, and rain. But here the desert is blooming. In the Middle East and North Africa, the quest to turn thousands of miles of desert into arable land has taken a backseat to containing an impending water shortage. While many countries in the region bicker over water rights, Libya has taken it upon itself to change its topography – turning sand into soil.

The Great Man-Made River, which is leader Muammar Qaddafi’s ambitious answer to the country’s water problems, irrigates Libya’s large desert farms. The 2,333-mile network of pipes ferry water from four major underground aquifers in southern Libya to the northern population centers. Wells punctuate the water’s path, allowing farmers to utilize the water network in their fields. The Libyan government says the 26-year project has cost $19.58 billion. Nearing completion, the Great Man-Made River is the largest irrigation project in the world and the government says it intends to use it to develop 160,000 hectares (395,000 acres) of farmland. It is also the cheapest available option to irrigate fields in the water-scarce country, which has an average annual rainfall of about one inch. “Rainfall is just concentrated in 5 percent of the [country’s] area, so more or less, 95 percent or 90 percent of our land is desert,” says Abdul Magid al-Kaot, minister of agriculture, during a PowerPoint presentation that accompanied a recent several-hour government tour of the project and farms outside the capital of Tripoli. “Water is more precious for us than oil. … Water here in Libya, it’s life.”

Just as Libya mines the desert for crude; they are doing the same for ‘fossil water’ – ice age water preserved in the porous holes of the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer. The massive aquifer stretches under Libya, Egypt, Chad, and Sudan. It includes four freshwater basins inside Libya that contain approximately 10,000 to 12,000 cubic kilometers (480 cubic miles) of ancient water buried as deep as 600 meters (2,000 feet) below the surface of the desert, reporters were told during the government presentation. Libya moves the precious resource from the ground to five giant above-ground reservoirs through pre-stressed concrete pipes, weighing 75-86 tons, that run 20 feet underground. Cranes weighing 450 tons operated on specially constructed roads to install the mammoth cylinders.

Other countries also drill for underground water, but none do so as intensely as Libya. The country is pulling up 2.5 million cubic meters per day, with the expectation of eventually pumping 6.5 million. Experts liken the project to moving 2.5 million Volkswagen Beetles more than 2000 miles every day – one car weighs roughly the same as a cubic meter of water, which is 2200 pounds. New drip irrigation techniques are being used to ensure water does not go to waste. More than 70 percent of the water is intended for subsided domestic agriculture, with the rest for citizen consumption. None is reserved for heavy industry, according to the government.

Although it is cheaper for Libya to pump the underground water than use desalination or import the substance, experts are wary of Libya’s decision to irrigate large scale farms with fossil water. “For Libya this is pretty expensive water. It’s not as expensive as desalinated water, but to irrigate with it is probably not cost effective at the purest sense,” says Aaron Wolf, professor and chair of the department of geosciences at Oregon State University. “If the farmer had to pay the full cost of pumping and shipping the water to them, they wouldn’t break even on their agriculture, that’s why other countries aren’t doing it.”

The Libyan government heavily subsidizes the water for farmers who pay about $0.62 for one cubic meter; slightly less than half the price citizens pay to drink it. “This is basically a wonder of the world, because it’s exactly like the pyramids – it’s huge and massive and probably not cost effective,” says Mr. Wolf. The Libyan government says reserves will last the country 4,625 years according to current rates of demand. But independent estimates indicate that the aquifer could be depleted in as soon as 60 to 100 years, says Stephen Lonergan, a professor of geography at the University of Victoria in Canada. “The main concerns with any non-renewable resource are the depletion rate and the dependency that is built up by using the resource,” he wrote in an e-mail to the Monitor. “The knock on these projects is that once the water runs out, there is a dependency that can only be met in the future by desalination or importing water,” Mr. Lonergan continues. Projects like this create “a legacy that may have short term gains but ultimately makes the country or region very vulnerable in the future.” For now, as giant sprinklers mist a 100,000 olive tree nursery in a greenhouse surrounded by sand on the outskirts of Tripoli, Libyan fields are flourishing.

Libyans like to call it “the eighth wonder of the world”. The description might be flattering, but the Great Man-Made River Project has the potential to transform Libyan life in all sorts of ways. Libya is a desert country, and finding fresh water has always been a problem. Following the Great Al-Fatah Revolution in 1969, when an army coup led by Muammar Al Qadhafi deposed King Idris, industrialisation put even more strain on water supplies. Coastal aquifers became contaminated with sea water, to such an extent that the water in Benghazi (Libya’s second city) was undrinkable. Finding a supply of fresh, clean water became a government priority. Oil exploration in the 1950s had revealed vast aquifers beneath Libya’s southern desert. According to radiocarbon analysis, some of the water in the aquifers was 40,000 years old. Libyans call it “fossil water”. After weighing up the relative costs of desalination or transporting water from Europe, Libyan economists decided that the cheapest option was to construct a network of pipelines to transport water from the desert to the coastal cities, where most Libyans live.

In August 1984, Muammar Al Qadhafi laid the foundation stone for the pipe production plant at Brega. The Great Man-Made River Project had begun. Libya had oil money to pay for the project, but it did not have the technical or engineering expertise for such a massive undertaking. Foreign companies from South Korea, Turkey, Germany, Japan, the Philippines and the UK were invited to help. In September 1993, Phase I water from eastern well-fields at Sarir and Tazerbo reached Benghazi. Three years later, Phase II, bringing water to Tripoli from western well-fields at Jebel Hassouna, was completed. Phase III which links the first two Phases is still under construction. Adam Kuwairi, a senior figure in the Great Man-Made River Authority (GMRA), vividly remembers the impact the fresh water had on him and his family. “The water changed lives. For the first time in our history, there was water in the tap for washing, shaving and showering,” he told the BBC World Service’s Discovery programme.

To get an idea of the scale of the Great Man-Made River Project, you have to visit some of the sites. Libya is opening up, but it’s still hard for foreign journalists to get visas. We had to wait almost six months for ours; but once we arrived in Libya, Libyans were eager to tell us about the project. They took us to see a reservoir under construction at Suluq. When it’s finished, the Grand Omar Mukhtar will be Libya’s largest man-made reservoir. Standing on the floor of such a huge, empty space is an awesome experience. Concrete walls rise steeply to the sky; tarring machines descend on wires to lay a waterproof coating over the concrete. Further west along the coast is the Pre-Stressed Concrete Cylinder Pipe factory at Brega. This is where they make the 4m-diameter pipes that transport water from the desert to the coast. It’s a modern, well-equipped factory, built specially for the Great Man-Made River Project. So far, the factory has made more than half a million pipes. The pipes are designed to last 50 years, and each pipe has a unique identification mark, so if anything goes wrong, engineers can quickly establish when the pipe was made. The engineer in charge of the Brega pipe factory is Ali Ibrahim. He is proud that Libyans are now running the factory: “At first, we had to rely on foreign-owned companies to do the work. “But now it’s government policy to involve Libyans in the project. Libyans are gaining experience and know-how, and now more than 70% of the manufacturing is done by Libyans. With time, we hope we can decrease the foreign percentage from 30% to 10%.”

Opening Markets

With fossil water available in most of Libya’s coastal cities, the government is now beginning to use its water for agriculture. Over the country as a whole, 130,000 hectares of land will be irrigated for new farms. Some land will be given to small farmers who will grow produce for the domestic market. Large farms, run at first with foreign help, will concentrate on the crops that Libya currently has to import: wheat, oats, corn and barley. Libya also hopes to make inroads into European and Middle-Eastern markets. An organic grape farm has been set up near Benghazi. Because the soil is so fertile, agronomists hope to grow two cereal crops a year. It is hard to fault the Libyans on their commitment. They estimate that when the Great Man-Made River is completed, they will have spent almost $20bn. So far, that money has bought 5,000km of pipeline that can transport 6.5 million cubic metres of water a day from over 1,000 desert wells. As a result, Libya is now a world leader in hydrological engineering, and it wants to export its expertise to other African and Middle-Eastern countries facing the same problems with their water. Through its agriculture, Libya hopes to gain a foothold in Europe’s consumer market. But the Great Man-Made River Project is much more than an extraordinary piece of engineering. Adam Kuwairi argues that the success of the Great Man-Made River Project has increased Libya’s standing in the world: “It’s another addition to our independence; it gives us the confidence to survive.” Of course, there are questions. No-one is sure how long the water will last. And until the farms are working, it’s impossible to say whether they will be able to deliver the quantity and quality of produce for which the planners are hoping. But the combination of water and oil has given Libya a sound economic platform. Ideally placed as the “Gateway to Africa”, Libya is in a good position to play an increasingly influential role in the global economy.

Contracts were awarded in 2001-02 for the next phase of Libya’s Great Man-Made River Project, an enormous, long-term undertaking to supply the country’s needs by drawing water from aquifers beneath the Sahara and conveying it along a network of huge underground pipes. In October 2001, the Great Man-Made River Authority (GMRA) awarded an $82 million contract for the construction of major new pumping facilities to a consortium led by Frankenthal KSB Fluid Systems. In January the following year, the Nippon Koei / Halcrow consortium was selected to provide the preliminary engineering and design works for Phase III of the operation, worth $15.5 million. The pumping station is scheduled to be completed in the summer of 2004 and KSB will subsequently be responsible for servicing the plant and providing technical support for one year after completion. The preliminary stages of phase III run until June 2005, though it is anticipated that GMRA will invite tenders for the detailed design and construction works towards the end of 2004. When completed, phase III, which requires an additional 1,200km of pipeline, will ultimately increase the total daily supply capacity of the existing system to 3.68 million m³ and provide a further 138,000m³/day to Tobruk and the coast.

Background

In 1953, the search for new oilfields in the deserts of southern Libya led to the discovery not only of the significant oil reserves, but also vast quantities of fresh water trapped in the underlying strata. The majority of this water was collected between 38,000 and 14,000 years ago, though some pockets are only 7,000 years old. There are four major underground basins. The Kufra basin, lying in the south east, near the Egyptian border, covers an area of 350,000km², forming an aquifer layer over 2,000m deep, with an estimated capacity of 20,000km³ in the Libyan sector. The 600m-deep aquifer in the Sirt basin is estimated to hold over 10,000km³ of water, while the 450,000km² Murzuk basin, south of Jabal Fezzan, is estimated to hold 4,800km³. Further water lies in the Hamadah and Jufrah basins, which extend from the Qargaf Arch and Jabal Sawda to the coast.

The GMR project – the world’s largest engineering venture – is intended to transport water from these aquifers to the northern coastal belt, to provide for the country’s 5.6 million inhabitants and for irrigation. Intended to be the showpiece of the Libyan revolution, Colonel Moammar Gaddafi called it the “eighth wonder of the world”. First conceived in the late 1960s, the initial feasibility studies were conducted in 1974 and work began ten years later. The project, which still has an estimated 25 years to run, was designed in five phases. Each one is largely separate in itself but will eventually combine to form an integrated system.

Pipe sections for the Great Man-made River Project, 1987, photo by Jaap Berk via WikiCommons

Pipe sections for the Great Man-made River Project, 1987, photo by Jaap Berk via WikiCommonsPhases I and II

The first and largest phase, providing 2 million m³/day along a 1,200km pipeline from As-Sarir and Tazerbo to Benghazi and Sirt, via the Ajdabiya reservoir, was formally inaugurated in August 1991. This was a massive undertaking, using a quarter of a million sections of concrete pipe, 2.5 million t of cement, 13 million t of aggregate, 2 million km of pre-stressed wire and requiring 85 million m³ of excavation, for a finished cost of $14 billion. The Tazerbo wellfield consists of both production and piezometric observation wells and yields around 1 million m³/day at a rate of 120L/s per well. Only 98 of the 108 production wells are used, with the others on stand-by. A collection network conveys the water to a 170,000m³ off-line steel header tank. From here, the main conveyance system is routed 256km to the north, to two similar header tanks at Sarir, where the second Phase I wellfield is located. A further 1 million m³ is produced here, using 114 of the 126 production wells, at an average flow rate of 102L/s per well. The wells at both Tazerbo and Sarir are about 450m deep and are equipped with submersible pumps at a depth of 145m.

From Sarir, two parallel, 4m-diameter pipelines convey the now chlorine-treated water to the 4 million m³ Ajdabiya holding reservoir, 380km to the north. The water flows from this 900m-diameter reservoir through two pipelines, one heading west to Sirt and the other north to Benghazi. Each pipeline discharges into a circular earth embankment end reservoir, with a storage capacity of 6.8 million m³ at Sirt and 4.7 million m³ at Benghazi, which have been designed to balance fluctuations in supply and demand. In addition, large reservoirs – 37 million m³ in the Sirt area and 76 million m³ in Benghazi – have been built to act as storage facilities for summer or drought conditions. Phase II delivers 1 million m³/day from the Fezzan region to the fertile Jeffara plain in the western coastal belt and also supplies Tripoli. The system starts at a wellfield at Sarir Qattusah, consisting of 127 wells distributed along three east-west collector pipelines and ultimately feeds a 28 million m³ terminal reservoir at Suq El Ahad.

Phase III

Phase III falls into two main parts. Firstly, it will provide the planned expansion of the existing Phase I system, adding an additional 1.68 million m³/day along with 700km of new pipeline and new pumping stations to produce a final total capacity to 3.68 million m³/day. Secondly, it will supply 138,000m³/day to Tobruk and the coast from a new wellfield at Al Jaghboub. This will require the construction of a reservoir south of Tobruk and the laying of a further 500km of pipeline. The preliminary engineering and design contract runs for 41 months and includes geotechnical and topographic surveys. The conceptual designs phase features extensive consideration of pipeline routing and profiling, hydraulics, pumping stations, M&E, control / communications system, reservoirs and other structures, corrosion control, power, operational support and maintenance provision. The evaluation of tenders for the detailed design is expected in the first quarter of 2005. The last two phases of the project involve the extension of the distribution network together with the construction of a pipeline linking the Ajdabiya reservoir to Tobruk and finally the connection at Sirt of the eastern and western systems into a single network. When completed, irrigation water from the GMR will enable about 155,000ha of land to be cultivated – echoing the Libyan leader’s original prediction that the project would make the desert as green as the country’s flag.

Key Players

The project is owned by the Great Man-made River Authority and funded by the Libyan Government. Brown & Root and Price Brothers produced the original project design and the main contractor for the initial phases was Dong Ah, with Enka Construction and Al Nah acting as sub-contractors. The preliminary engineering and design contractor for Phase III is Nippon Koei / Halcrow consortium. The Frankenthal KSB consortium won the pumping station construction and technical support contract and SNC-Lavalin are responsible for the pipe production plant O&M. Libyan Cement supplied the concrete. Thane-Coat and Harkmel provided pipeline coating services and Corrintec supplied the cathodic protection system. Thyssen Krupp Fördertechnik provided technical services for the excavation planning and a number of local companies carried out elements of the construction and ancillary work.

Tuesday, April 12, 2011 at 02:52PM

Tuesday, April 12, 2011 at 02:52PM